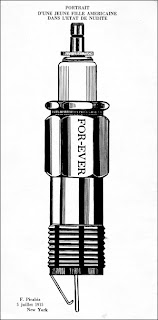

Artwork by Francis Picabia

The

Fragility Of Memory In A Postmodern Age

In the

twenty-first century, we know more about memory than ever before, but trust its

resources less. The idea of memory, conceived as the keystone of identity for

the nineteenth century, has been reconceived as the debris of lost identities,

the free-stones of aging memory palaces that have fallen into ruins. Since the

last quarter of the twentieth century, the topic has inspired intense interest

among historians, literary critics, folklorists, sociologists, anthropologists,

psychologists, and neurobiologists. Across the curriculum, scholars are as one

in noting that memory is easily and often remodeled, almost always distorted,

and hence unreliable as a guide to the realities of the past. The idea of

memory, therefore, is noteworthy for its fragility, vulnerable as it is not

only to the vagaries of the mind but also to social, political, and cultural

forces that would alter or obliterate it.

On the

edge of fragile memory lies nostalgia, the most elusive of memory's protean

forms and one beginning to receive critical attention. An admixture of

sweetness and sorrow, it expresses a longing for a vanishing past often more

imaginary than real in its idealized remembrance. Nostalgia exercised a

powerful appeal in the Romantic sentiments of the nineteenth century, tied as

it was to regret over the passing of ways of life eroded by economic and social

change, a generalized popular enthusiasm for innovation, and rising

expectations about what the future might hold. Nostalgia was the shadow side of

progress. Chastened by the disappointments of the twentieth century, however,

the idea of progress has fallen on hard times, and nostalgia presents itself as

an even more diffuse longing for a fantasy world that never existed (for

example, the classless society in Communist propaganda). So reconceived,

nostalgia has come to be criticized as a dangerous surrender to anarchistic

illusion that contributes to memory's vulnerability to exploitation and misuse.

Situated

at an interdisciplinary crossroads, the idea of memory has yet to promote an

exchange between humanists and scientists, though they make their way along

converging avenues of research. Scientists have moved away from Freud's claim

about the integrity of memory's images. Steady research in psychology over the

course of the twentieth century exposed the intricacies of the mental process

of remembering, which involves complex transactions among various regions of

the brain. For psychologists, remembering is conceived as a dynamic act of

remodeling the brachial pathways along which neurons travel as they respond to

sensory stimuli. The images of memory are encoded in neural networks, some in

short-term and some in long-term configurations, and so are mobilized as

conscious memories in multifold and continually changing ways. Memory resides

in these ephemeral expressions, and its images are constantly subject to

revision in the interplay of well-established patterns and chance circumstances

that governs recall.

Some

neuroscientists propose that memory is an adaptive strategy in the biological

life process. Drawing on Charles Darwin's theory of natural selection, the

American neuroscientist Gerald Edelman (1929–) argues that there is a selective

process by which memory cells cluster in the neuronal groups that map neural pathways.

He identifies two repertoires of such clusters in the gestation of the brain,

one, primarily genetic, in embryo, and the other, primarily adaptive, after

birth. They establish the categories of recognition through which the brain

thenceforth processes external stimuli, though these categories are continually

modified as the brain adapts to new life experience. In this sense, each act of

recollection is a creative process that entails a reconfiguration of synaptic

connections. There is an intriguing analogy between Edelman's two stages of

memory cell formation and the mnemonist's two-step reinforcement of memory in

repertoires of places and images. There is a resonance as well between

Edelman's notion of the brain's mapping of neural pathways and Halbwachs's

conception of the topographical localization of social memory. Both affirm the

constructive nature of the act of memory in the interplay of recognition and

context.

(This article was found on the web and I thought to share)

No comments:

Post a Comment